Octopus Color Receptors

The eyes of cephalopods like octopus, squid, and cuttlefish possess only one kind of photoreceptor, implying that they are colorblind, being able to see only in greyscale. Cryo-electron microscopy analyses reveal adaptations that facilitate the octopus chemotactile receptor's evolutionary transition from an ancestral role in neurotransmission to detecting. The octopus eye works very differently than the human eye, which let light in through slitted pupils that scatter it like a rainbow.

If you've ever had your pupils dilated, you may have noticed. This exceptional color vision is made possible by their complex eyes, which contain a large number of color receptors called cones. These cones are responsible for detecting different wavelengths of light and transmit this information to the brain, which then processes it and enables the octopus to perceive and respond to its environment.

What Color Is An Octopus - colorscombo.com

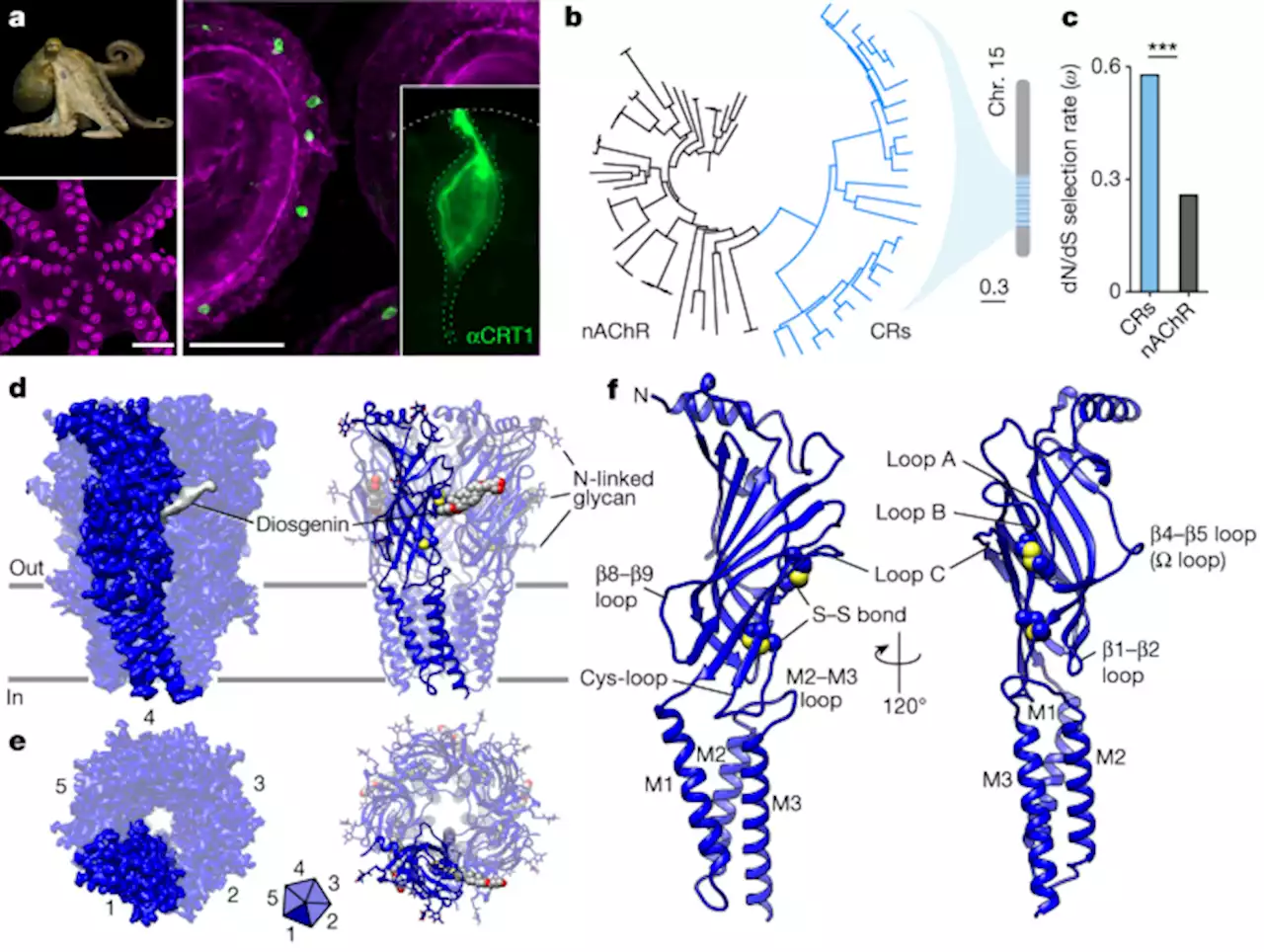

Here, we exploit octopus CRs to probe the structural basis of sensory receptor evolution. We present the cryo. For decades, biologists have puzzled over the paradox that, despite their brilliantly colored skin and ability to rapidly change color to blend into the background, cephalopods have eyes containing only one type of light receptor, which basically means they see only black and white.

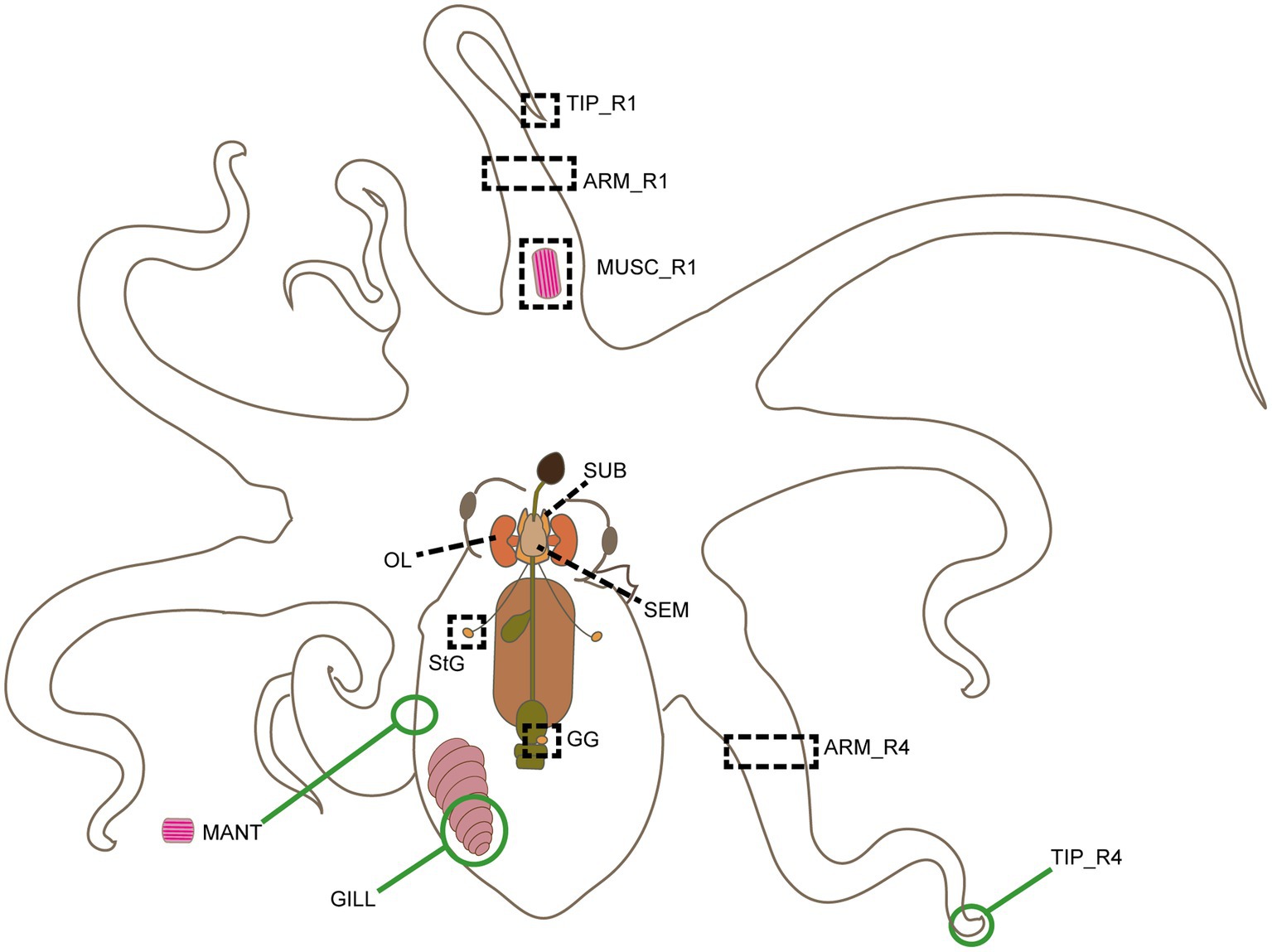

Octopus and squid use cephalopod-specific chemotactile receptors to sense their respective marine environments, but structural adaptations in these receptors support the sensation of specific. We found that dispersed, dermal light sensitivity contributes to a direct response of Octopus bimaculoides chromatophores to light. We call this chromatophore response light-activated chromatophore expansion (LACE).

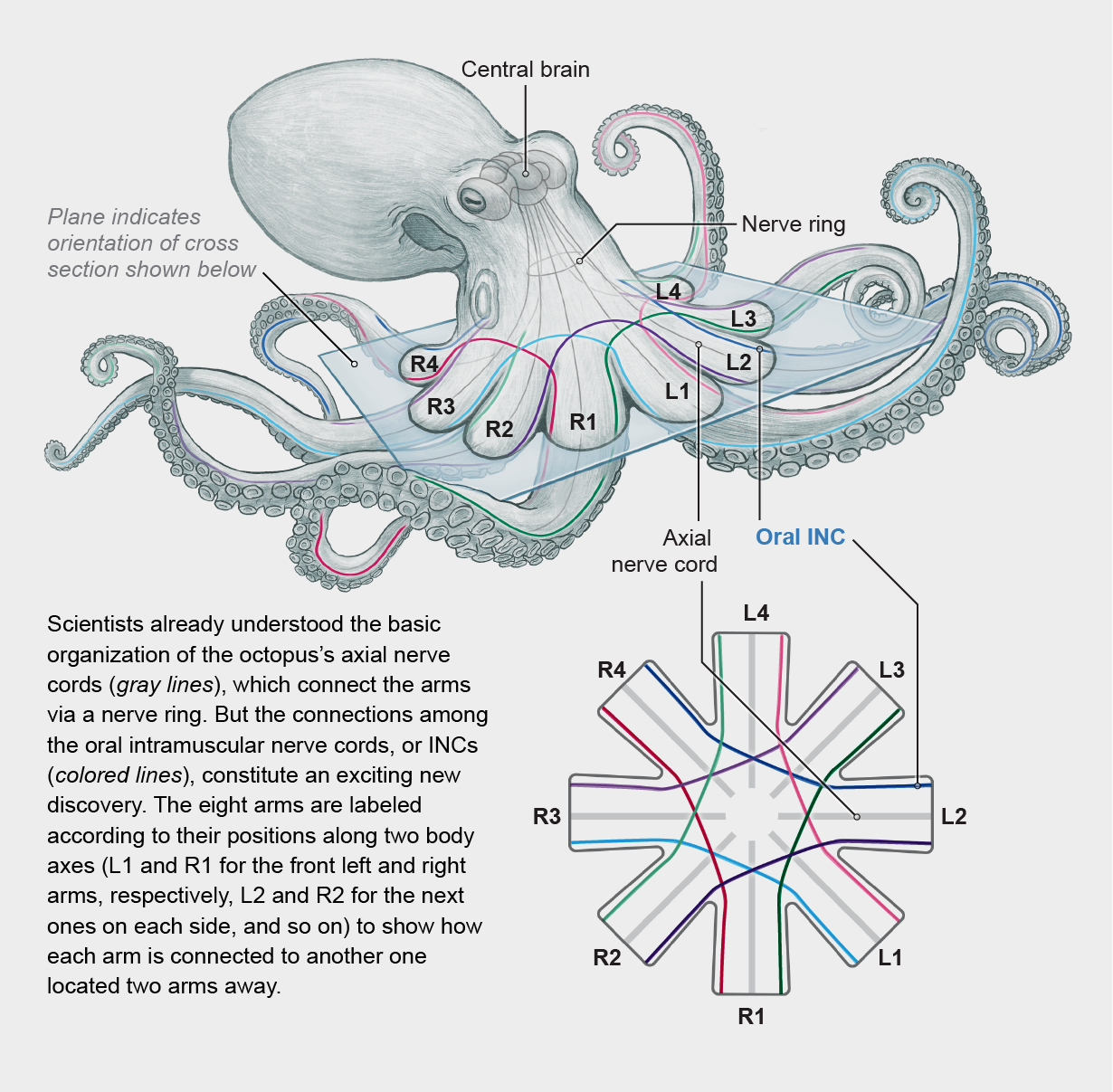

Octopus Nervous System Diagram

LACE behavior in isolated octopus skin shows that the skin can sense and respond to light directly. The octopus can alter its appearance in seconds, using specialized sensory receptors to detect the surrounding environment. Color.

An octopus uses its eyes to determine what color and pattern to mimic, but they lack some of the receptors in their eyes that humans use to see color. Scientists aren't sure why, but as you may remember from the Open Water course, an object that is red on the surface may appear brown or black at depth.